Dear Amelia,

When I was a girl I wanted a horse. I actually had a friend who had a Welsh pony. Spending the night with her was special because I got to ride her horse. Now, I didn't want her horse --I wanted a horse just like "Black Beauty" or "Ginger." I read that book and loved it. I imagined Black Beauty was mine. I imagined Merryweather was mine. I imagined Ginger was mine, and I imagined the perfect home and the love I would give them.

Now, I am MANY years from that first reading of "Black Beauty" and loved reading it again. I encourage you to do what I did. Imagine each of the horses were yours. Imagine you ARE the horses. I am certain you will remember this book as long as I have.

Ms Hesse

When I was a girl I wanted a horse. I actually had a friend who had a Welsh pony. Spending the night with her was special because I got to ride her horse. Now, I didn't want her horse --I wanted a horse just like "Black Beauty" or "Ginger." I read that book and loved it. I imagined Black Beauty was mine. I imagined Merryweather was mine. I imagined Ginger was mine, and I imagined the perfect home and the love I would give them.

Now, I am MANY years from that first reading of "Black Beauty" and loved reading it again. I encourage you to do what I did. Imagine each of the horses were yours. Imagine you ARE the horses. I am certain you will remember this book as long as I have.

Ms Hesse

Article about "Black Beauty"

MORE About "Black Beauty!"

Black Beauty generated a lot of excitement when it hit shelves on Nov. 24, 1877. After all, no one had written a book from an animal’s point-of-view before. But that’s what Anna Sewell did. Black Beauty is the story of a horse told from the horse’s perspective. It was a unique concept in the late-18th century. That’s because, at that time, people viewed horses as machines. Horses transported people and cargo, fought wars, and plowed fields. The idea that horses felt pain or emotions was extraordinary to many in Western society. In short, few people thought about horses the way Anna Sewell did.

But Sewell’s viewpoint was different from a lot of peoples’ due to an ankle injury she sustained as a teenager. The damage was severe enough that Sewell had to rely on a horse-drawn cart for all her transportation. Through this dependency, Sewell thought of her horse as more than a piece of machinery. And she decided to tell a story that would help others see horses in a different light.

It took many years for Sewell to write that story. She did so by scribbling it on small scraps of paper or by dictating the manuscript to her mother, Mary Wright Sewell. Mary Wright was herself an author. She’d published a few books of poems and stories for children. Mary Wright helped transcribe and edit her daughter, Anna’s, draft. But Anna wasn’t writing her story for children. She wanted to change how people viewed and treated horses. To have this impact, Anna knew she needed to reach adults.

The animal, Black Beauty, endures incidents of kindness and cruelty. At one point the horse laments about his human handlers, “What right had they to make me suffer like that?” The book became a bestseller. In the U.S., more than one million copies of the book were in circulation within two years of its publishing. More importantly to Anna, though, Black Beauty achieved her goal of bringing about more humane treatment of horses.

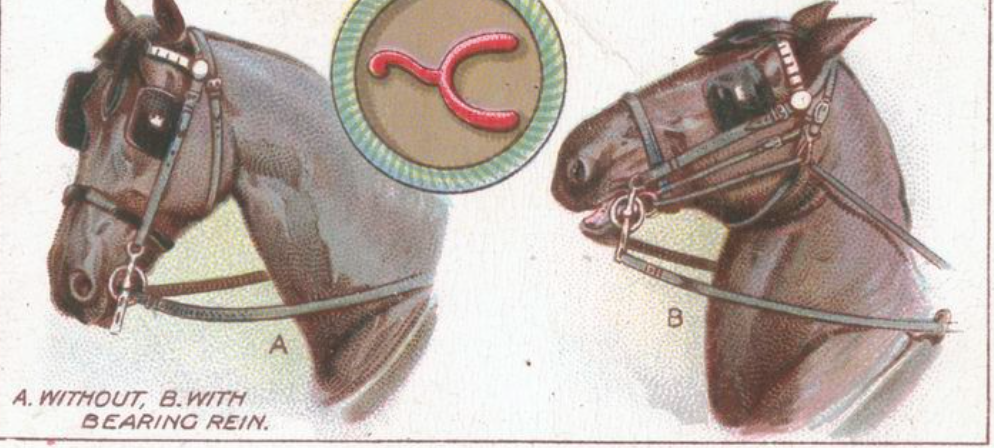

The clearest example of this influence is with the “bearing rein.” A “bearing rein” forces a horse’s head closer to its chest. The device created a look that pleased many in upper society, but it also made it difficult for horses to breathe. Within a few years of Black Beauty’s release, many Western countries stopped using “bearing reins.”

But Anna Sewell didn’t live to see the effect her story had on how people treated horses. She died on April 25, 1878, five months after Black Beauty was published. It was her only book.

The legacy continues. People still read Black Beauty. The book’s sold more than 50 million copies. These days, though, most who read Black Beauty are children. After all, at 59,635 words, it’s short enough for kids to enjoy. (The average Harry Potter book is nearly 155,000 words.) And in today’s motorized world, treatment of horses isn’t as pressing an issue as it was in Anna Sewell’s.

Perhaps more relevant to us these days is the story of why and how Anna Sewell wrote Black Beauty. She wanted to change minds. To do so, the writer abandoned conventional storytelling and wrote from an animal’s perspective. She persevered through physical challenges. In the end, she altered history and produced one of the most popular books ever published.

But Sewell’s viewpoint was different from a lot of peoples’ due to an ankle injury she sustained as a teenager. The damage was severe enough that Sewell had to rely on a horse-drawn cart for all her transportation. Through this dependency, Sewell thought of her horse as more than a piece of machinery. And she decided to tell a story that would help others see horses in a different light.

It took many years for Sewell to write that story. She did so by scribbling it on small scraps of paper or by dictating the manuscript to her mother, Mary Wright Sewell. Mary Wright was herself an author. She’d published a few books of poems and stories for children. Mary Wright helped transcribe and edit her daughter, Anna’s, draft. But Anna wasn’t writing her story for children. She wanted to change how people viewed and treated horses. To have this impact, Anna knew she needed to reach adults.

The animal, Black Beauty, endures incidents of kindness and cruelty. At one point the horse laments about his human handlers, “What right had they to make me suffer like that?” The book became a bestseller. In the U.S., more than one million copies of the book were in circulation within two years of its publishing. More importantly to Anna, though, Black Beauty achieved her goal of bringing about more humane treatment of horses.

The clearest example of this influence is with the “bearing rein.” A “bearing rein” forces a horse’s head closer to its chest. The device created a look that pleased many in upper society, but it also made it difficult for horses to breathe. Within a few years of Black Beauty’s release, many Western countries stopped using “bearing reins.”

But Anna Sewell didn’t live to see the effect her story had on how people treated horses. She died on April 25, 1878, five months after Black Beauty was published. It was her only book.

The legacy continues. People still read Black Beauty. The book’s sold more than 50 million copies. These days, though, most who read Black Beauty are children. After all, at 59,635 words, it’s short enough for kids to enjoy. (The average Harry Potter book is nearly 155,000 words.) And in today’s motorized world, treatment of horses isn’t as pressing an issue as it was in Anna Sewell’s.

Perhaps more relevant to us these days is the story of why and how Anna Sewell wrote Black Beauty. She wanted to change minds. To do so, the writer abandoned conventional storytelling and wrote from an animal’s perspective. She persevered through physical challenges. In the end, she altered history and produced one of the most popular books ever published.